Ding-a-ling. Financial Santa is in the house, but does he also bring rate cuts?

Unlike the real Santa, who brings his gifts late in the year, the Financial Santa, tends to begin a couple of months earlier.

Mon 30 Oct 2023

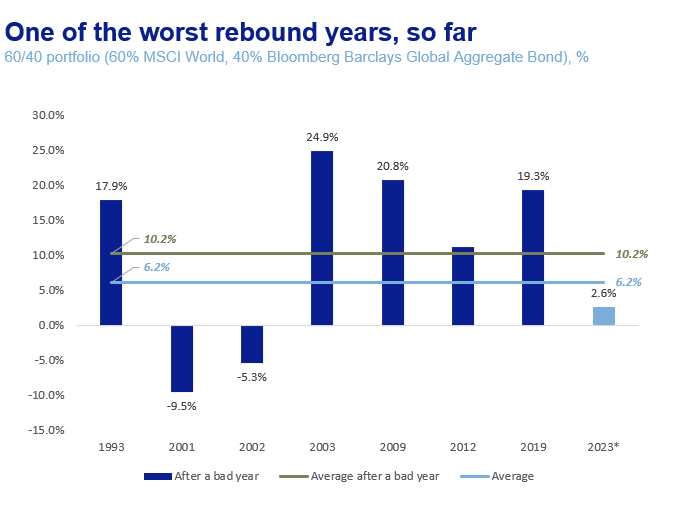

After 2022, the annus horribilis, it was widely assumed that 2023 would be a rebound year. However, up to the end of October, a 60/40 (MSCI World/Bloomberg Barclays Global Bond Index), was up a mere 2%, very far from the average uplift of 5% and 9% experienced in a rebound year.

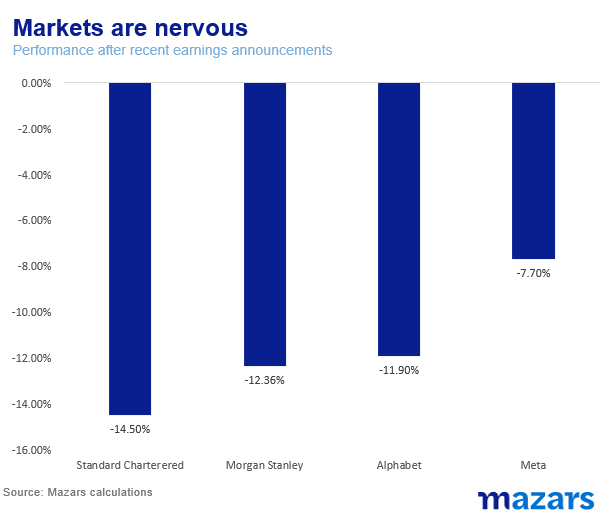

Last week was one of the worst weeks this year for equities, with many companies (Alphabet, Meta, Standard Chartered) losing value following below-expected forward earnings projections. Investors found refuge in bonds, with the US 10y yield coming off the 5% watermark. Meanwhile, the S&P 500 is now in correction (-10%) territory.

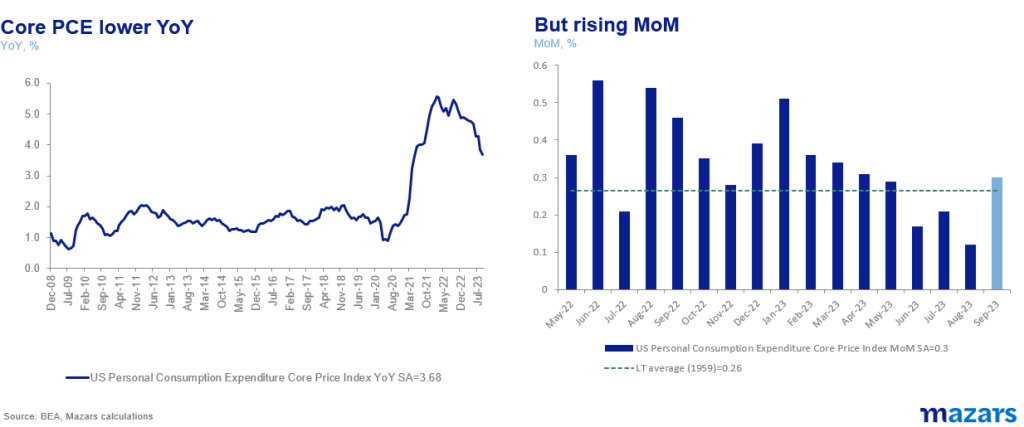

On the face of it, the pullback doesn’t make much sense. US inflation is mending, with core PCE remaining stable at 3.7%, despite strong Q3 growth figures in the US. The Fed has all but confirmed that they are on pause mode. And geopolitical tensions didn’t escalate nearly as quickly as they might have.

So why the risk-off sentiment last week? And why haven’t portfolios rebounded as much as they have historically?

The reasons for last week’s selloff lie behind the headline numbers:

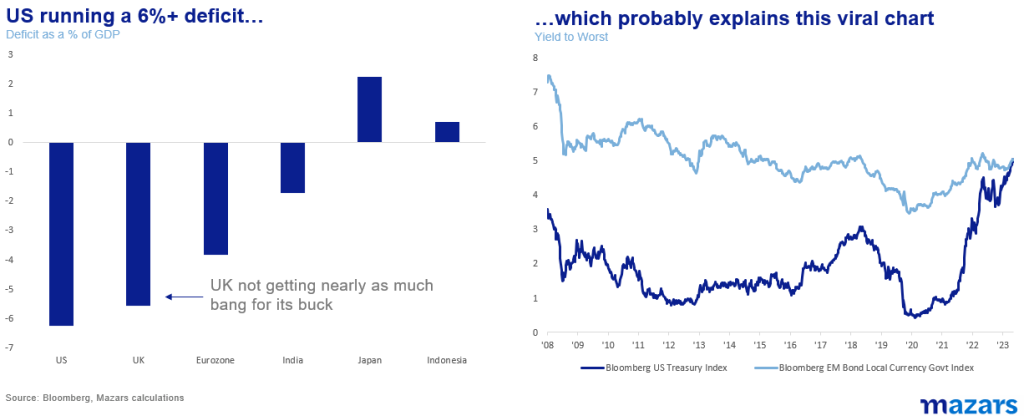

For one, the US might be growing at a faster pace than everyone else, but it’s borrowing heavily to do so. Presently, it’s running a 6%+ deficit, roughly double that of Europe. It’s debt to GDP is projected by the IMF to reach 137% by 2028.

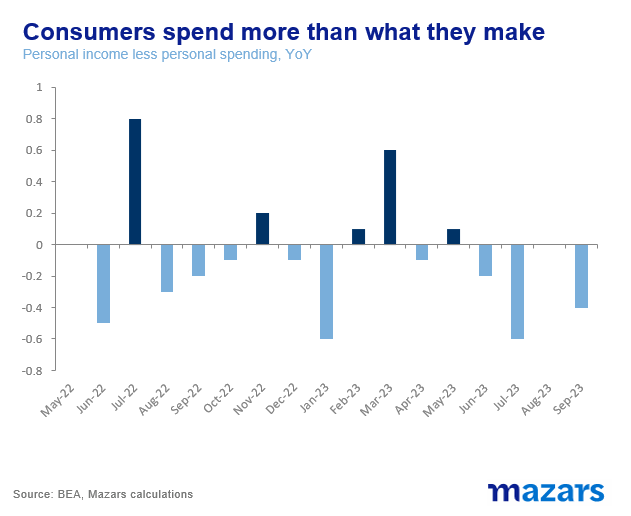

Even if you own the world’s reserve currency, there’s bound to be some pushback when borrowing that heavily. Bill Clinton’s last Treasury Secretary and Barack Obama’s Director of the National Economic Council, Larry Summers, went on record saying that the Fed will eventually have to weigh in on the growing debt pile, and perhaps raise rates further. Consumers aren’t holding back either. For the past few months, they have been spending more than they are making.

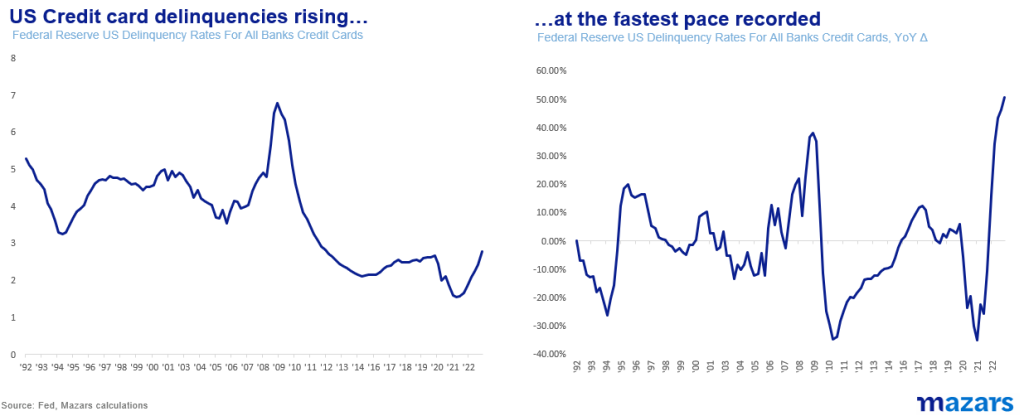

It’s no surprise then that credit card delinquency rates, which have returned to just above their historical average, are rising at the fastest pace on record, solidifying the argument that the extra cash from the pandemic is all but spent.

And while inflation might be petering out, the latest core inflation numbers (Core Personal Consumption Expenditures, the Fed’s preferred gauge of inflation) suggest that prices are beginning to pick up again.

Second, earnings are problematic. While earnings announcements so far haven’t been that bad (78% of companies are beating projections), the violent market reactions to the results of Alphabet, Standard Chartered, Meta and Morgan Stanley suggest that investors are nervous about earnings growth going forward, and probably for good reasons. After all, while earnings from operations went up, bottom line earnings growth remained flat, suggesting that a growing proportion of earnings is going towards making interest payments. If that’s happening in the world’s largest companies, businesses with smaller capitalisations are bound to have bigger problems.

Third, geopolitical uncertainty remains at the forefront of market participants’ thinking. Oil prices might have fallen back to within a range (West Texas Crude $84 at the time of writing), but there are currently two wars raging, both of which have global implications for commodity prices.

Fourth, we remain in quantitative tightening mode. While easily forgotten, especially as we enter a rate hike hiatus, the Fed is reducing the amount of money in the markets. It’s hard enough to have a proper rebound year when rates remain above 5%; things are more likely to get worse while the Fed is actively reducing liquidity.

Fifth, larger risks remain. Early in the year, markets got a scare when several US peripheral banks went under. Presently, the US banking system alone has more than $650bn of unrealised losses on bonds, a record amount. Any sort of alarm that could cause depositors to pull away money could force banks to liquidate assets, not only have to realising losses, but also dumping more bonds into an already saturated market.

This was a really long way of saying that “geopolitics and high interest rates at these levels of debt continue to weigh on financial markets”.

So, there are plenty of fundamental reasons for investors to be worried and not entirely buy the headline story, i.e., stronger growth and lower inflation. With Quantitative Tightening remaining in effect, it’s hard to have a proper bullish rebound.

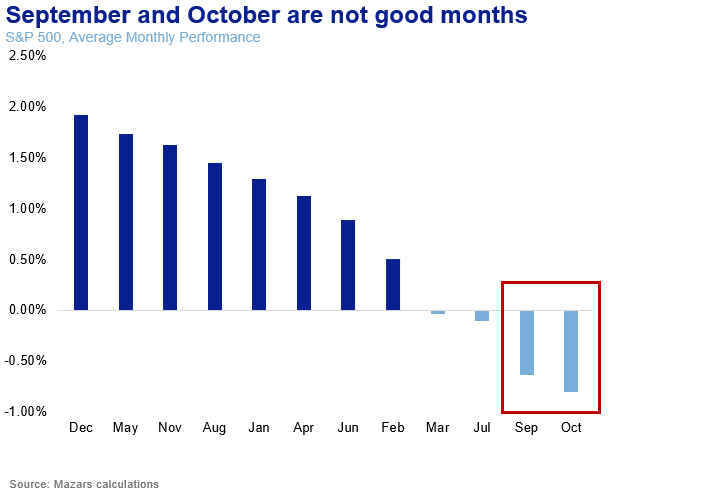

However, we should not write off 2023 just yet. September and October are historically the worst months of the year by far. This means that regardless of the view we currently hold, there’ remains a likelihood that this is the worst this year has to offer. Can the balanced portfolio rise again before the year’s out? The answer is yes, we can still get our customary Santa Rally.

Santa Rallies are less about long term fundamentals, and more about present market sentiment, flows and positioning.

The S&P 500 forward P/E is now at 19x, below the 20x mark and right at its 5-year average. Stocks aren’t heavily overbought. Meanwhile, short positions in US Treasuries have risen to very high levels. Presently, there are 4.7 million short contracts on US Treasuries, according to the Commodity Futures Trading Commission data, roughly 20% higher than its previous peak in 2019. A market event that drives shares lower could also ignite a short squeeze on Treasuries, as investors rush towards safe haven assets.

And that is the beauty of a balanced portfolio. With the Fed disentangling itself from the yield curve, correlations are returning to their historic norms. A negative market event may cause equities to fall and bonds to rise, while a positive event would allow for a rally in equities, with bonds already providing a good yield for investors.

George Lagarias – Chief Economist

This website uses cookies.

Some of these cookies are necessary, while others help us analyse our traffic, serve advertising and deliver customised experiences for you.

This website cannot function properly without these cookies.

Analytical cookies help us enhance our website by collecting information on its usage.

We use marketing cookies to increase the relevancy of our advertising campaigns.