The new great debate: minimum global corporate income tax?

Corporate structures

The new great debate: minimum global corporate income tax?

Fri 07 May 2021

The new U.S. Secretary of Treasury, Janet Yellen, has garnered this week’s tax spotlight with her support and request for the world to support a minimum global corporate income tax. This would apply to the largest and most profitable businesses (numbering around 100), with the suggestion that the minimum rate to be applied to be 21%, and be based on where they do business (a form of global formulary apportionment).

One’s reaction to this is either ‘yay’ or ‘ouch’ depending on which side of the fence one actually sits.

Could this finally be the solution to what Yellen calls the “30 year race to the bottom” in her virtual speech to the Chicago Council on Global Affairs on 5th April 2021?

You may recall that for many years, the U.S. touted one of the highest corporate income tax rates in the world at 35%, although profits retained overseas could escape this tax until remitted to the US. Such loftiness in tax rates prevailed despite many countries pre-Covid for many years scrambling to bottom out or drop their rates in the spirit and hope of enticing world business, industry and production to locate profitable activities in their location.

But arguably post-Covid, this so-called race to the bottom might be said to be a race back up to the top as nations large and small struggle to balance their budgets and fill their coffers for much needed public support and subsidy to aid recovery from the pandemic.

Does such a position for a global minimum tax actual stand a chance to gain consensus and materialise, or is it a bit ‘rainbows and unicorns’ dreamy?

Consensus on tax matters has proven to be rather challenging as we are already experiencing with the likes of digital taxation, for example.

Here, a perfect illustration of countries agreeing that yes, there should be a digital tax but the method, allocation and apportionment of such a tax is yet to rally accord. Rather, nations (large and small, alike) are busy unilaterally entering into force their own domestic digital taxation systems.

Is it possible then to achieve international harmony on something as important to a jurisdiction as the ability to differentiate itself and manage economic development/investment through the way it sets its corporate income tax rate? Would your country support a minimum global corporate income tax? If yes, at what rate and why?

Around 135 countries have been sent the US global tax proposals and many must be weighing up their impact in contrast to the OECD pillar 1 and 2 proposals and their current position.

The UK currently has a corporation tax rate of 19%, with a proposal to increase this to 25% in 2023. However if the basis of apportionment for large companies changes from the current method (based on profits arising in the location where business is done) to something based on a formula according to where revenue is recognized, further analysis may be required. The effectiveness of Ireland’s 12.5% corporate tax rate and the benefits of reduced taxes from patent box and research & development incentives in a number of jurisdictions, will all need to be reconsidered.

The minimum tax rate is proposed in the OECD pillar 2 stream of work, which reportedly may be set at 12.5%, which is significantly below the US proposals. However, taking the OECD Pillar 1 and 2 proposals together, there is potential for significant complication for a large number of companies. If the US proposals limit the impact to 100 companies, complexity for the majority might well be avoided. However, as noted above, particular countries will want to assess the particular impact on their revenues, bearing in mind there are no limitations on the range of companies to which the US proposals would apply.

Both the OECD and US global tax solutions would require agreement internationally, and most likely some change in the way domestic rules work. For example, it may not be difficult for a low tax jurisdiction to identify the entities within its jurisdiction that might be subject to a minimum tax rate and apply that rate to those entities. That way it might retain the advantages of the lower rate for other taxpayers, without losing out on tax revenue from the largest multinationals. Limiting these new proposals to the 100 largest global companies does seem to have some attractions from a revenue authority perspective. It is notable that Luxembourg, Ireland and the Netherlands have cautiously welcomed the US proposal, noting that the precise level of a minimum tax has yet to be agreed.

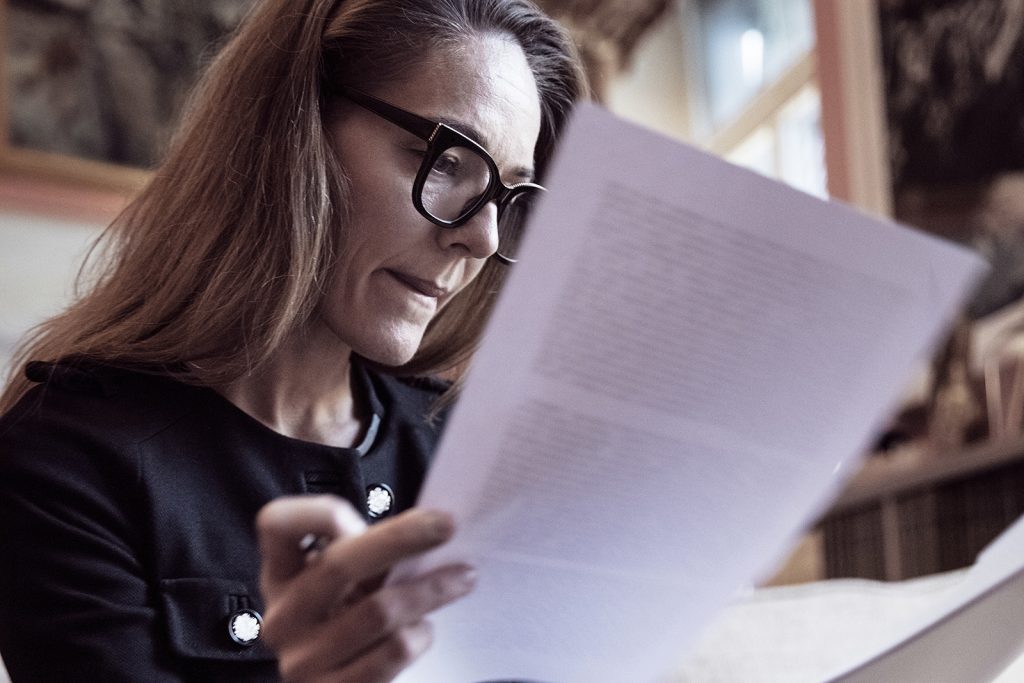

From the perspective of large business, there may be some active analysis by those who are at the margins of the thresholds for the different proposals, and some lobbying to be done by those caught by one proposal but not the other. From the perspective of business, one might expect the solution which provides the simplest method of administration and the greatest certainty on outcome would be the most attractive. Those businesses will also be keen to understand the impact on their effective tax rate and how that will impact its ability to raise finance and to compete in the market place.

As regards developing countries, and specifically African countries, it is worth reassessing whether a “race to bottom” is really applicable, when the African average corporate tax rate was 27.5% in 2020, compared to 23,2% in the OECD zone[1]. In a sense, the management of tax rates and incentives is a useful tool for medium and smaller sized economies to attract large business to help fund local jobs and infrastructure. The imposition of a minimum tax rate may take away this possibility making it more difficult for such jurisdictions to compete in the global market place.

Of course, tax on company profits is the form of taxation being considered in the US and OECD proposals for global tax reform. There are many other ways government’s raise revenue or provide investment incentives, so the imposition of a global minimum tax on corporate profits will only be one aspect to assess when considering the financial implications of business location and market entry requirements.

For a further discussion of how your business should be preparing for upcoming changes in global tax policy, please get in touch with your usual Mazars contact.

[1] https://www.oecd.org/fr/fiscalite/politiques-fiscales/statistiques-impot-sur-les-societes-deuxieme-edition.pdf

Want to get notified when new blog posts are published?

Subscribe